One of the most well-known rules of kashrut is the separation of meat and dairy. This practice, rooted in Jewish tradition, prohibits cooking, eating, or benefiting from any mixture of the two. The rule extends to utensils, dishes, and even waiting periods between consuming one and the other. Its origins trace back to biblical texts, emphasizing distinct categories in food preparation and consumption.

Introduction:

Kashrut (Jewish dietary laws) dictate what observant Jews eat and how they prepare food. One of the most fundamental rules is the prohibition against mixing milk and meat. Jews keep foods like dairy (milk, cheese, etc.) and meat (beef, chicken, etc.) apart. Orthodox Jews (who follow traditional Jewish law very strictly) take great care to obey this rule in all aspects of life.

Biblical Sources about Meat and Milk

The prohibition against mixing milk and meat comes from the Torah, the Hebrew Bible. In fact, a specific command appears three times in the Torah: “Do not cook a kid in its mother’s milk.”

The Talmud (Chullin 115b) discusses why this phrase is repeated three times. According to the sages, each instance teaches a different aspect of the prohibition: one bans cooking meat and milk together, another forbids eating them together, and the third prohibits deriving benefit from such a mixture.

A “kid” here means a baby goat. This exact line is twice in the Book of Exodus and once in Deuteronomy. For example, Exodus 23:19 says you should not boil a young goat in its mother’s milk. By repeating it three times, the Torah shows that this is a significant law.

Although the Torah specifically mentions a young goat and its mother’s milk, rabbinic interpretation expands this as a general prohibition against mixing all meat and dairy. The verse is brief, but it became the basis for a general rule: Jews must not cook or eat any meat and dairy together. The Torah doesn’t give a detailed explanation there, but it sets the foundation for this important dietary law.

Talmudic and Rabbinic Interpretations of Meat and Milk

Because the Torah’s command is short, Jewish sages (rabbis) discussed and explained it further in the Talmud (the collection of Jewish oral teachings). They asked: What exactly does this law cover? From the three mentions of the verse, the sages learned three separate rules about meat and milk:

The Three Main Rules

- No cooking meat and dairy together: You should not cook or boil a piece of meat in milk (even if you don’t plan to eat it).

- No eating meat and milk together: You shouldn’t eat a meal that mixes dairy and meat (for example, no cheeseburgers, which combine meat and cheese).

- No benefit from a meat-milk mixture: You shouldn’t even gain any benefit from a mixture of milk and meat. This means one shouldn’t sell it or feed it to pets because that would still make use of the forbidden combo.

Expanding the Law to All Kosher Animals

The rabbis also clarified what types of food the Torah was talking about. The Torah’s wording mentioned a goat, but the sages explained that it applies to all kosher animals that produce milk.

This expansion is based on Talmudic reasoning (Chullin 113b), where the sages argue that the Torah often gives examples that illustrate a broader principle. Since cows, sheep, and goats are all kosher mammals that produce milk, the prohibition applies to them as well.

In other words, it’s not just goats – it includes cows, sheep, and other kosher mammals. So mixing beef (from a cow) with cheese is just as forbidden as mixing goat meat with milk. The Torah used the goat example simply because that was a common scenario in ancient times.

What About Poultry?

What about other animals, like chickens or other birds? Birds don’t make milk at all, so some early authorities (such as one sage named Rabbi Yossi in the Talmud) felt that the Torah’s law might not apply to poultry. However, the wise rabbis decided to extend the rule to birds as well as a protective measure.

This is confirmed in the Mishnah (Chullin 8:1), which states that ‘it is forbidden to eat poultry cooked with milk by rabbinic decree.’ Rabbi Yossi, one of the sages, initially argued that poultry should not be included in this ban since birds do not produce milk, but the majority opinion extended the prohibition.

This is a rabbinic addition to prevent confusion. Therefore, traditional Jewish law forbids eating chicken with dairy too, even though there is no “mother’s milk”. For example, an Orthodox Jew would not eat chicken parmesan (a dish that mixes chicken and cheese), treating it as non-kosher, even though there is no mention of chicken in the original verse. The rabbis made sure that all meat (whether from a cow, lamb, or chicken) stays separate from any milk products.

Extra Precautions to Keep Meat and Dairy Apart

The sages added other guidelines to help people keep meat and dairy apart. They ruled that even if meat and milk are not cooked together, you shouldn’t eat them at the same time or off the same plate. They even cautioned people not to sit at the same table with someone eating the opposite (one having meat, the other dairy) unless some clear separation is in place – this is to avoid accidentally sharing or mixing the foods. These extra rules are like “fences” to protect the basic Torah law. They make it easier for people to remember and follow the main rules.

Waiting Between Meat and Dairy

The rabbis also discussed timing: they taught that you should wait a certain amount of time between eating meat and then eating dairy.

This practice is based on Talmudic discussion (Chullin 105a), where Mar Ukva states, ‘My father would wait a full day between eating meat and dairy, but I wait only until the next meal.’ Later authorities, such as the Rambam (Maimonides, Mishneh Torah, Hilchot Ma’achalot Asurot 9:28), codified the waiting period as six hours, though customs vary.

In one Talmud story, a sage would wait “until the next meal” after eating meat before having any milk. This evolved into the common practice of waiting about six hours after eating meat to eat dairy. (Some Jewish communities have slightly different customs, like waiting three hours or one hour, but many Orthodox Jews stick with roughly six hours.)

The reason is that meat can leave fats and tastes in your mouth or bits between your teeth, and waiting ensures the two foods won’t mix inside your body or mouth. On the other hand, after eating dairy first, the wait time is shorter – many just rinse their mouth and can eat meat after a brief pause (sometimes about an hour or less) since dairy doesn’t linger as long. All these sage interpretations highlight the seriousness of the milk-and-meat rule, transforming a single-line commandment into a detailed practical law.

Why Does This Law Exist?

It’s important to note that the rabbis also talked about why this law might exist. They offered different explanations (called commentaries).

A Law of Pure Faith: A “Chok”

But in the end, the rabbis acknowledged that we follow this law simply because God commanded it, even if we don’t fully understand the reason.

In Hebrew, we call such a law a “chok” – a divine decree that we follow purely out of faith.

The Ramban (Nachmanides, Commentary on Deuteronomy 14:21) describes this as a ‘chok,’ meaning a law whose reasoning is not explicitly given. He explains that while some mitzvot have clear rationales, others, such as the prohibition against mixing meat and milk, are decrees meant to instill discipline and obedience to God’s will.

For Orthodox Jews, the exact reason is less important than the obedience to God’s word.

Teaching Compassion

One idea is that the Torah wanted to teach compassion: using a mother’s milk – meant to give life to her baby – to cook the baby itself would be cruel. This view sees the law as a way to avoid cruelty to animals.

Rashi (Commentary on Exodus 23:19) echoes this sentiment, explaining that boiling a young animal in its mother’s milk is an act of insensitivity, as the milk is meant to nurture the animal, not be used in its destruction.

Spiritual Symbolism (Kabbalah)

Another perspective from later mystical teachings (Kabbalah) views meat and milk as two opposite spiritual forces:

- Meat represents strength (strictness, judgment).

- Milk represents kindness (nurturing, life).

- Mixing them disrupts balance, so they must remain separate.

The Zohar (Parashat Mishpatim, 125b) explains that meat represents ‘Gevurah’ (strict judgment), while milk represents ‘Chesed’ (loving-kindness). Mixing them disrupts spiritual harmony, so they must remain separate.

Possible Health Reasons

Some even thought there might be health or hygiene reasons, though this is debated.

Practical Applications of Keeping Meat and Dairy Separate

Keeping Meat and Dairy Separate:

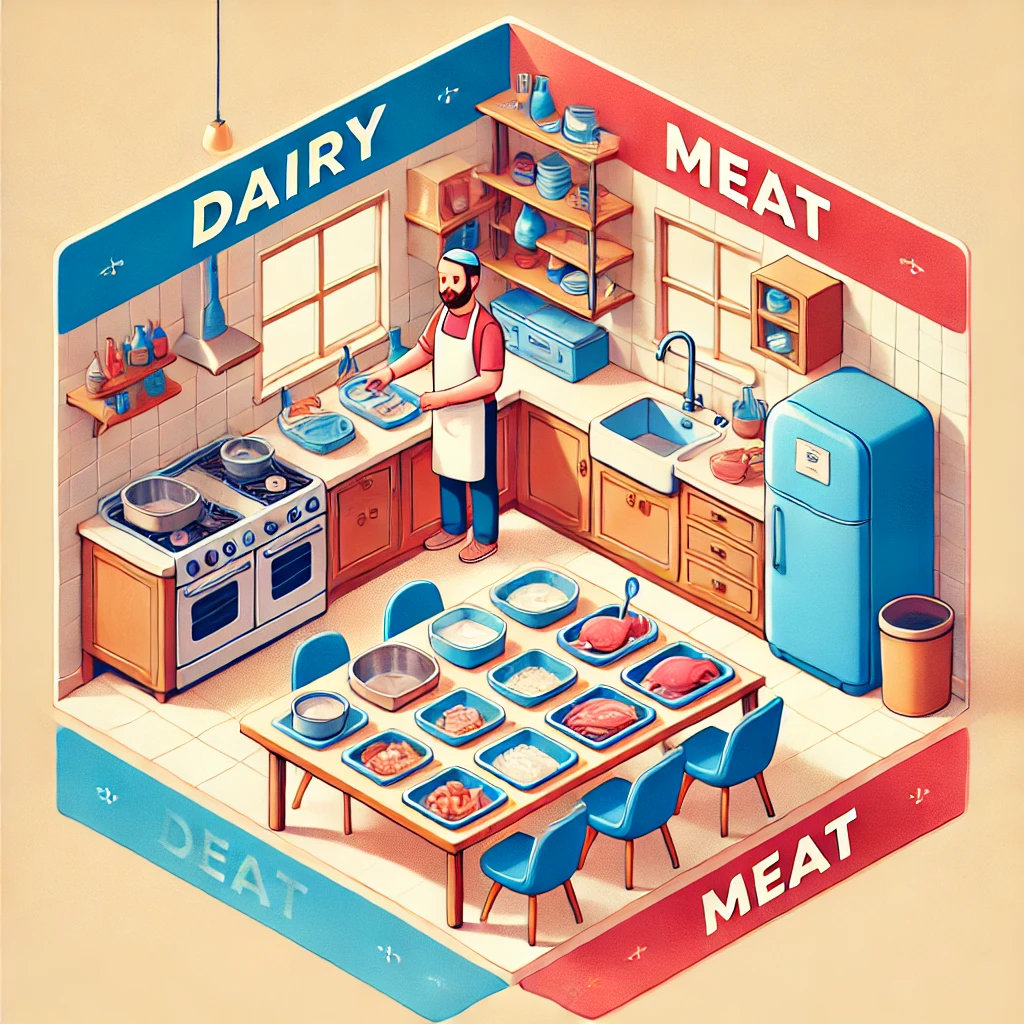

In a kosher household, the milk-meat rule affects how the kitchen is set up and how food is prepared. To make sure they never mix the two types, families use completely separate equipment for dairy and meat. You might open an Orthodox Jewish kitchen cabinet and see two sets of dishes: one set of plates, cups, and silverware for when they eat dairy foods and another set for when they eat meat foods.

The same applies to pots, pans, and cooking utensils. For example, people designate one “meat pot” for boiling soup or chicken and use a separate “dairy pot” only for dishes like mac and cheese. Many households store these sets in separate cabinets, often labeling or color-coding them (commonly blue for dairy and red for meat) to prevent mistakes.

They use separate sponges to wash the dishes and separate towels to dry them so that no tiny bits of meat or dairy stick to the opposite set. Many kosher kitchens include two sinks or a divided sink, using one side to wash meat dishes and the other for dairy dishes. All of this careful arrangement prevents any chance that meat residue will touch dairy items or vice versa.

Meal Planning

Families plan their meals as either a meat meal or a dairy meal, but never both at the same time. For instance, they might have a dairy breakfast (cereal with milk or a cheese omelet) and avoid meat like bacon or sausage. If they have a meat lunch or dinner (say, chicken or beef), they will not serve any dairy products during that meal.

A dessert for a meat meal has to be dairy-free, such as fruit, sorbet, or non-dairy ice cream made with soy or coconut milk. Likewise, if they have a dairy meal (like cheesy pasta or pizza with cheese), they won’t have meat in that meal or right after. This way, milk and meat don’t end up in the stomach together.

Waiting Time

Observant Jews maintain a gap between eating meat and dairy. A child in an Orthodox family might eat a hamburger for lunch and know that if they want ice cream later, they must wait several hours. This ensures any meat traces are gone before dairy is eaten.

It becomes a normal routine: “I had a hot dog at 1 PM, so I’ll wait until the evening before I have a glass of milk.” Waiting isn’t too hard once you get used to it, and it’s a clear way to separate the foods.

At the Table

Even when eating different types of food at the same table, care is taken. If one person is having a dairy meal and another is having a meat meal, they use separate tablecloths or placemats. They are careful not to share or spill into each other’s food.

However, families usually schedule meals so that everyone eats the same category (all dairy or all meat) together. This keeps things simple and avoids any accidental mixing.

Cooking and Serving

Cooks who keep kosher are mindful of recipes and ingredients. They never intentionally mix butter, milk, or cheese into a meat dish. If a recipe calls for both, they modify it to stay kosher.

For example, butter on a steak or cheese on a burger is not allowed. Instead, they might use non-dairy margarine for cooking the steak or skip the cheese on the burger. Many traditional Jewish recipes have evolved to use alternatives so they remain kosher.

A classic example is that you won’t find cheeseburgers or creamy beef stroganoff on a kosher menu. However, you might find similar dishes made in a permissible way, like a burger with lettuce and tomato but no cheese or a stroganoff made with dairy-free creamer.

Pareve Foods

There is a whole category of foods called pareve (or parve, pronounced PAHR-veh), which means neutral. Pareve foods contain neither meat nor dairy, so they can be eaten with either side. Common pareve foods include fruits, vegetables, grains, fish, eggs, and nuts.

For example, bread is usually pareve, so you can have bread with a meat meal or a dairy meal. Salad, pasta, and many desserts can also be pareve if made without milk ingredients. Using pareve foods is very helpful in a kosher kitchen.

If you bake a cake with no dairy in it (no butter or milk), that cake is pareve and can be served as dessert after a meat dinner. If you cook vegetables in vegetable oil instead of butter, they stay pareve and everyone can enjoy them with any meal. Some families even have a third set of dishes or utensils just for pareve cooking, though this is not required as long as the pareve items don’t mix with the others.

All these practical steps — separate dishes, careful meal planning, waiting between foods, and using pareve options — ensure meat and dairy never meet in a kosher kitchen or in an observant Jew’s mouth. It becomes a natural part of life for those who keep kosher. Even kids grow up learning which plate is for what and asking, “Is this snack dairy or meat?” before deciding what else they can eat. It might sound like a lot of rules, but families that keep kosher follow them every day as a normal routine to respect their traditions and faith.

Modern-Day Considerations

Kosher Laws in Modern Times

Even today, with grocery stores and processed foods, Orthodox Jews strictly follow these laws. Modern food production and labeling help kosher-observant people know what they can eat.

Kosher Certification Symbols

A major help is kosher certification symbols on packaged foods. These small logos appear on wrappers, cans, or boxes to indicate whether the food is kosher. They also classify the food as meat, dairy, or pareve.

One common symbol is “OU” inside a circle, representing the Orthodox Union, a major kosher certifying agency. If a package has a plain “OU”, it usually means the food is pareve (neutral), containing no meat or dairy.

If you see “OU-D” or a “D” next to the symbol, the product contains dairy or was made on dairy equipment. A symbol with an “M” or the word “Meat” means the product contains meat or was processed with meat.

Different Kosher Symbols

There are many kosher certification symbols used worldwide. Some include a K in a star, the word “Kosher” in Hebrew, or other unique designs. Despite their differences, they all serve the same purpose—assuring customers that the food follows kosher laws, including keeping milk and meat separate.

Checking for Kosher Labels

Orthodox Jews always check for these symbols when shopping. If they want cookies after a Sabbath lunch with chicken, they look for pareve or dairy-free cookies, avoiding those with butter.

If a cookie package has a dairy symbol, they know not to eat it after a meat meal. This simple labeling system helps people maintain kashrut without confusion.

Kosher Food Production Standards

Kosher certification agencies send inspectors (called mashgichim) to food factories. They ensure companies follow the rules, especially when producing both dairy and non-dairy items.

If a company makes both, it must thoroughly clean the machinery between batches or have separate production lines. This prevents any cross-contamination between dairy and non-dairy products.

Thanks to this system, a person keeping kosher can confidently buy a can of soup or a candy bar knowing whether it’s suitable for their meal.

Kosher Restaurants and Food Establishments

Kosher restaurants follow strict separation rules. A kosher restaurant will be either meat or dairy, but never both at the same time.

For example, a kosher pizzeria uses only dairy and pareve ingredients like cheese and vegetables, with no meat at all. Customers can enjoy cheese pizza or ice cream, but no pepperoni since it’s both meat and usually non-kosher.

A kosher grill restaurant, on the other hand, serves burgers, steaks, or chicken, but never includes cheese, butter, or milkshakes on the menu. Each type of restaurant ensures complete separation of dairy and meat.

Kosher Fast Food

In some cities, both meat and dairy kosher restaurants exist, but they maintain separate kitchens and often have different supervisors to prevent mixing.

Even fast-food chains in Israel adjust their menus to follow kosher laws. A kosher McDonald’s in Israel serves Big Macs without cheese and avoids mixing milk into meat sauces.

If they offer dessert or coffee, they use non-dairy creamer or serve it separately to keep meals kosher. This allows Orthodox Jews to eat out while following Kashrut laws.

Modern Kosher Kitchens

Many Orthodox families invest in kitchen designs that help them keep kosher. If they can afford it, they might have two ovens—one for meat and one for dairy.

Some also have two dishwashers or wash dishes separately by hand to avoid residue mixing. Special kosher refrigerators have separate sections or alarms to help maintain food separation.

To make things easier, many label containers or use color-coded stickers on utensils. Stores even sell cutting boards in red and blue sets for meat and dairy or spatulas marked “Meat Only.” These modern tools help prevent mistakes.

Role of Kosher Certification Agencies

Kosher certification agencies, such as OU, OK, Star-K, and others, play a big role in kosher life. They inspect food factories and provide symbols on food packaging to confirm products meet kosher standards.

These agencies also publish kosher product lists and label items made on dairy equipment (“DE”) since strict observers treat those as dairy.

With kosher certification, a wide variety of foods—from bread to cereal to candy—can be bought with confidence, ensuring no hidden mixing of milk and meat.

Education and Community Awareness

Teaching kashrut starts early. Children in Orthodox Jewish schools learn about meat and milk separation from a young age.

They practice using color-coded plates in classroom kitchens or toy kitchens. By the time they grow up, it becomes second nature to ask, “Is this fleishig or milchig?” (Yiddish for meat or dairy).

Even with modern foods and global cuisine, Orthodox Jews remain dedicated to keeping meat and dairy separate. With clear labeling, specialized kitchens, and kosher supervision, this mitzvah (commandment) continues to be observed with deep commitment, guided by centuries of tradition.

Scientific and Health Perspectives

People sometimes wonder if there’s a scientific or health reason behind the ban on mixing milk and meat. From a scientific standpoint, eating them together is not poisonous or physically dangerous.

Millions of people eat cheeseburgers or pepperoni pizza without any immediate health problems. There is no medical rule stating that the body cannot digest these foods at the same time.

Historical Health Speculations

In history, some speculated about possible health concerns. In medieval times, a few Jewish scholars suggested that mixing milk and meat could harm the body.

They observed that meat is heavy and takes longer to digest and thought adding milk might upset the stomach or slow digestion. However, these ideas were based more on theory than scientific proof.

Religious Discipline, Not Biology

Modern nutrition science finds no special problem with eating meat and dairy together. The restriction is not based on health concerns but on religious discipline.

For Orthodox Jews, the reason for keeping milk and meat separate is spiritual, not medical. It is a divine commandment, followed with faith, regardless of scientific explanations.

A Commandment, Not a Health Rule

Kosher laws encourage cleanliness and careful food preparation, but the milk-meat rule wasn’t given for health reasons. It is a holy commandment meant to be followed as part of Jewish faith.

Orthodox Jews do not separate meat and dairy for diet or health reasons—they do so because God commanded it. Even if science proved that eating a cheeseburger is completely healthy, an Orthodox Jew would still not eat it. The focus is on following the Torah, not personal health benefits.

Ethical and Spiritual Perspectives

Some view this law as a moral lesson against cruelty. Cooking a baby animal in the milk meant to nourish it feels harsh and unnatural. Keeping meat and dairy separate may encourage compassion and sensitivity toward animals.

Others see it as spiritual symbolism. In mystical thought, meat (which comes from death) represents severity and judgment, while milk (which gives life) symbolizes kindness. Mixing them represents opposing energies clashing, making it spiritually unwise.

While these ideas add meaning, they are not the primary reason Jews keep this law. They are deeper interpretations, but the foundation remains God’s commandment.

A Religious Commitment

There is no strong scientific necessity to separate milk and meat. Unlike avoiding poisonous foods, this rule is followed purely as a religious commitment. Any health benefits are incidental rather than the reason for the law.

Jewish children are taught: We keep milk and meat apart because this is what God asks of us in the Torah. By following this rule, Jews bring holiness into something as simple as eating.

A Law That Shapes Daily Life

A single Torah verse has shaped an entire way of cooking and eating. For an Orthodox Jewish family, keeping milk and meat separate is a normal part of life.

From checking food labels at the store to using the right dishes at home, these rules remain deeply ingrained. Rooted in ancient text, expanded by rabbinic wisdom, and kept alive through daily dedication, this mitzvah continues to be a core part of Jewish life.

Frequently Asked Questions:

The Torah says, “Do not cook a kid in its mother’s milk.” From this, Jewish tradition teaches that meat and dairy shouldn’t be cooked, eaten, or even served together.

Many wait 6 hours after eating meat before eating dairy. Some wait 1 or 3 hours, depending on family or community tradition. But after eating dairy, you usually don’t need to wait before eating meat—rinse your mouth and wash your hands. However, some do wait a token time, such as 30-60 minutes, to separate the eating.

“Meat” means beef, lamb, chicken, and anything made from them (like broth or fat). “Dairy” means milk, cheese, butter, or yogurt. Fish and eggs are not meat or dairy—they’re called “pareve.”

No. In a kosher kitchen, people use separate sets of dishes, silverware, and even sinks or dishwashers—one for meat and one for dairy. If something gets mixed by mistake, you usually ask a rabbi what to do.

Pareve means “neutral.” These foods are not meat or dairy—like fruits, vegetables, grains, eggs, and fish. You can eat pareve foods with either meat or dairy, which makes them very helpful when planning kosher meals.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why can't you mix meat and dairy in kosher cooking?

In kosher dietary laws (Kashrut), mixing meat and dairy is prohibited based on the Torah's commandment not to 'cook a kid in its mother's milk.' This is interpreted as a general separation between all meat and dairy products to avoid any form of mixing.

How long should I wait between eating meat and dairy?

The waiting period varies by tradition. Many Ashkenazi Jews wait 6 hours after eating meat before consuming dairy, while some Sephardic Jews wait only 1 hour. After dairy, a shorter wait (often just rinsing the mouth) is required before eating meat.

Can I use the same utensils for meat and dairy if I wash them?

No, kosher kitchens require separate sets of utensils, cookware, and dishes for meat and dairy to prevent cross-contamination. Even thorough washing isn't sufficient according to kosher law.

Are there any foods that are considered neutral (pareve) in kosher rules?

Yes, pareve foods like fruits, vegetables, grains, eggs, and fish (without scales isn't kosher) can be eaten with either meat or dairy meals, making them versatile in kosher cooking.

Is chicken considered meat in the meat-dairy separation?

Yes, poultry (like chicken and turkey) is treated as meat in kosher law and cannot be mixed with dairy. The separation applies to all kosher land animals and birds, not just red meat.